All Categories • Continuing Committee • Organized Play • Rules Committee • Deck Designs • Virtual Expansions

Card Extras • Special Events • Tournament Reports • Everything Else • Spotlight Series • Contests

Strategy Articles

Hindsight: Premiere

by Charlie Plaine, Chairman

15th January 2014

Welcome to Hindsight, my weekly series where I take a look back at previous expansions for the Star Trek: Customizable Card Games with a fresh eye. My goal is examine the decisions made in each of these expansions using modern eyes and design sensibilities in order to learn from those decisions. As mentioned in the announcement article, this is not an attempt to create a new game. Instead, I’m looking to better understand the game and how it can be improved.

This week, we’re starting where it all began: First Edition Premiere. As the initial product for First Edition, Premiere made a lot of decisions that would shape how the game would be played and evolve over the next twenty (20) years. Of course, many of the original rules have been updated or replaced since this product was released, but we are still building on the foundations laid down with this initial product.

Premiere (First Edition)

Released in November 1994

363 Cards (121 Common, 121 Uncommon, 121 Rare)

Card Types Introduced

Artifact, Dilemma, Equipment, Event, Facility, Interrupt, Mission, Personnel, and Ship.

Lessons Learned

As this is the first article of the series, I’ll provide a brief explanation about the purpose of each section as I introduce them. In this section, I will talk about the potential mistakes and/or missed opportunities in the expansion, and determine what we can learn from those issues.

1. Not all cards are created equal.

This is probably the biggest elephant in the room, but the lack of a resource system in First Edition is a flaw in the game's design. It's understandable, though, because card games were brand new when First Edition was being created. There were only a handful of examples, and I suspect the designers put a priority on simplicity of resources in order to put their complexity into other areas (seeding).

The problem isn't really the lack of a resource system as much as that it creates a system where all cards needed to be equal in value. Unfortunately, that wasn't the case for Premiere. The game was designed with a basic resource model (play one, draw one) but had a wide inequity in card value. You're almost always making a better decision by playing Jean-Luc Picard over Benjamin Maxwell. (Note: To be fair, you can always create a scenario where playing Maxwell is a better decision. But in general, in most cases, that won't be true. When designers talk about "strictly better," that is the context in which it's meant. A guy with ![]() and four skills is "strictly better" than a guy with no staffing and the same four skills.)

and four skills is "strictly better" than a guy with no staffing and the same four skills.)

And in truth, this is a problem we are still struggling with today. Adding a true resource system would fundamentally alter how First Edition works. In fact, this was the approach taken when creating Second Edition (which we'll discuss next week). Instead, the designers have (and still are) creating cards like Office of the President in order to add value to pre-existing cards. The creation of a free play mechanic provides a way to exceed the natural resource limit (play one) provided by the game. And it's an innovative idea, but it can lead to escalation. Design has struggled recently with finding a good balance between the rate of play and the investment of resources. It's something we'll continue to struggle with as we move forward.

The lesson here though is that design has to always be conscious of ways to add value to cards. The resource system is built upon the assumption of a flat power level, and that's just impractical to maintain. Variations in power make games exciting and thus, in general, more fun. Instead of striving to create a flat power level (on a card by card basis), we need to strive to find ways to add value to cards. But we need to do so in a way that is mindful of power creep and play escalation.

2. Federation creep.

It's natural for a show to focus on a group of heroes over its lifetime. We tune in to watch week after week because of these characters and their exploits. When you create a game based on such a property, it's natural for these heroes to be well represented. However, a good show also needs villians and characters that oppose the heroes, and the game has to capture those too.

Premiere does a good job of representing obstacles for their heroes to face (in the form of dilemmas), but did a huge disservice to the non-Federation characters. I alluded to this problem in the most recent Make it So challenge, although in the context of missions, as Federation creep. It's a natural instinct, especially in the context of a story based game, to favor the heroes and the main characters. But this can't be done if it means that the other factions aren't going to have similar opportunities. For example, the most skill-dense personnel for the Klingons in Premiere is B'Etor, with five (5) skills; the most skill-dense personnel for the Romulans in Sela with four (4). By comparison, the Federation has four (4) personnel with five (5) or more skills. In general, the Federation has more and better personnel in Premiere than either the Klingons or the Romulans.

The lesson here is to make sure that we make all of the affiliations have "stars" and not just those that were shown on the screen. We can create characters with skills based on the story, but we also have to make sure that we are creating powerful characters across all of the affiliations. Of course, it's possible to take this too far, as happened in the case of Gozar from The Next Generation. We should have skill-dense and skill-light characters in all affiliations, even if that means we need to extrapolate skills for some characters.

3. Some things should not be done.

Here's an uncomfortable truth: designers always try to push boundaries. It's probably human nature to want to make things new and different than what's come before, as a way to express creativity. This is especially true for rookie designers, in that they almost always join a team and immediately want to do wildly different things. But here's another uncomfortable truth: humans do not like change. A game has to have consistency in its life, or you risk dooming your game to a slow death as your players drift away.

But as important as it is to be consistent from release to release, you also have to evolve the game. Designers have to walk the line between keeping things familiar (providing comfort) and creating new tricks (evolving the game). This means that designers have to experiment and try new things, and some of those things will make it into the game. The problem with Premiere is that they didn't really have any way of knowing exactly how bad some things could be. I've heard before that your greatest weakness is your greatest strength taken too far, and I think this aptly applies to First Edition. The game allows you to do so much, but it can fall apart when you try to do too much. The reality is that 1E is still a game and needs to enable good game play, even if that means some things need to be prohibited.

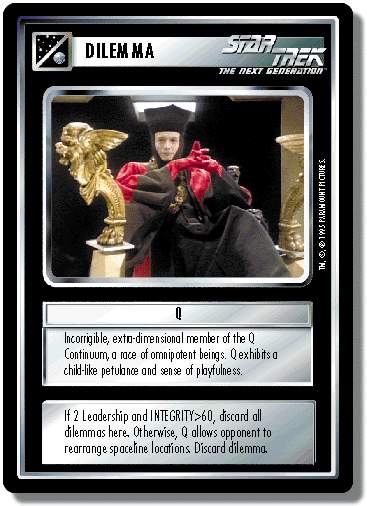

For example: rearranging the space line. This is a cool bit of flavor and it's a neat representation of the power of a character like Q. However, the mechanics of doing so are time intensive and logistically difficult. In casual games this might not matter, but in organized play it can be a nightmare. It is something that should not be done, even though it is cool, in order to make the game better. Similarly, there are cards that effectively read "you don't get to play anymore" - cards like The Devil. The lesson here is to be wise, and remember that being able to do something doesn't mean that its a good idea: always something important to keep in mind as we continue to innovate and move the game forward.

Good Stuff

I don't want these articles to be all about what was wrong with these expansions, so I want to take a few moments to highlight some of the good things each one accomplished. These are things that were particularly well done and that we should make sure we can continue to do moving forward.

1. Provide a clear differentiation of card types.

It's important for each card type to have a specific role to play in the game, and Premiere established fairly clear guidelines for the different card types. While events and interrupts are a little muddy (as they tend to be throughout First Edition's life), it's fairly clear how each of the card types function, and has remained clear as the game has evolved.

2. Non-Aligned as support only.

Premiere provided a few Non-Aligned cards in order to provide support for all of the affiliations, and that is an excellent role for that affiliation. Later expansions (as we will see) will turn Non-Aligned into an entity that can function on its own, which introduces additional problems to the game. Creating a faction that only serves as support was a wise decision.

Conclusion

I hope you've enjoyed this look back at First Edition's debut in Premiere. I'd like to read your feedback on the format of this series, how it can be improved, and what you think about the topics discussed. In addition, please share stories with us about your memories from playing in this era, and what the game was like in that time.

Next week, I'll be back to take a similar look at Second Edition. Thank you for reading!

Discuss this article in this thread.

Back to Archive index